Ted Mullin Talk: Reflections from the Iron Curtain Trail

Below is a transcript of a talk I gave in January 2011 at Carleton College on my experience biking the Iron Curtain Trail with a Ted Mullin Fellowship from the History Department. The talk was part of a presentation on the Fellowship experience alongside co-recipient and friend Hunter Knight, who hiked the Camino de Santiago across Spain. Enjoy!

Thank you for coming. I want to open with a look at this map. [Facebook world map] This was created in December by an intern at Facebook, who plotted every friendship on the social networking site. Each line represents a friendship between two people. The result is a remarkably accurate world map that roughly shows the outline of continents, and even countries. Look a little closer, and you’ll notice that the entirety of Russia and China seem to be missing. And there are also significant, but not unsurprising dark spaces in the Sahara and the Amazon.

Modern Europe is my field of study, so naturally, I wanted a closer look at the region. And immedietely, I couldn’t help but notice very stark differences on the map that lined up with political borders. You can see the outline of Spain pretty clearly, here’s the borders of Lithuania, and this line is roughly where the Soviet Union met its satellite countries, and today marks the frontiers of Belarus and Ukraine.

But there’s another line on this mp that is not an international border, but a distinct split within a country. This line cuts through the middle of Germany, almost exactly where the country was divided into East and West until 1990. This map, created 20 years after reunification, shows a political line that no longer exists. This line, now a section of the Iron Curtain Trail, is what I set out to explore last summer.

I started in Travemünde, Germany, on the Baltic Sea, and biked to Waldmünchen, Germany, on the Czech border. I was on the road for 40 days and 40 nights with my computer, camera, and a few changes of clothes. I covered more than 1600 kilometers (or a thousand miles) and only crashed one and a half times. I changed trains 9 times to get to Berlin and back, to meet 1 Member of Parliament.

I like numbers, information, and maps, and I collected a lot of these on my trip, and I developed a habit of throwing them around when I got back. After all, the were answers to most questions people asked, a good way to sum up any given accomplishment or landmark. These conversations didn’t last very long or mean much, and after a while, I knew that I was just hiding behind the numbers. So much of my journey was a solitary experience-(I sometimes went days without meeting someone who spoke good English)-and I realized I had no idea how to talk about it. Today, I’m hoping to go a little deeper.

The final count from my odometer was one thousand, six hundred and eighty-eight kilometers, which is one thousand, forty-eight miles. This distance includes the entire length of the German-German Border, the Berlin Wall Trail, and then some. Almost all of this distance was covered on bike. Yes, some of it involved pushing and scrambling, and one memorable road in the Czech Republic even featured steps. But, every inch of this way was under my own power. I got dehydrated, I lost weight, I worked just about as hard as I ever had to make that distance, and to make it worthwhile.

This was an intensely physical experience, but it was exactly what I had been hoping for. One of the goals of my project was to find a way to connect with he painful legacy of the Iron Curtain, even though I have no lived experience of the Cold War. The physically demanding nature of my tour was a primitive, but deeply important way of doing this. And distance became relative as I found myself asking, really, what would another 20 kilometers be at the end of the day? On a bike, all you need is a little patience and the will to keep spinning. Slow, sometimes difficult travel made the land I passed through so much more real, and allowed me to face my own obstacle in the same place where Germans had been divided by walls and barbed wire.

I made about two and a half million revolutions of the wheel. It starts in the torso, then glutes, hip flexors, quads, hamstrings, through my knees and calves, all contracting simultaneously to push down on the pedals that worked the chain (slick and sticky with grease and dirt), to spin the wheels. Tires gripping all kinds o ground, constantly moving forward. And when I got back to campus in the Fall, I discovered I could finally ride with no hands.

All summer, I was an outsider. I hardly know any German. I was born in 1989, just months before the Wall fell and far too young to know about it. And I am American, a stranger to the European experience and mindset of division, and historically speaking, regular warfare. Many people I met were surprised to find me on my own in the middle of Germany. I stayed with an elderly woman whose surprise didn’t need translating when I told her I was only twenty.

Sometimes this was hard. When the sun got low, the rhythm of the ride was interrupted, and there wasn’t much to do but hunker down and rest up. It was then that uncertainty gnawed at me. Were my plans realistic? Is my bike safe in that garage? How the hell am I going to make it through Bratislava in one piece? So I counted the days to go and ate dinners alone, which bothered me most in a tiny village called Lassahn, where I was treated to a sunset view over a lake on the summer solstice, but found myself surrounded by placid, elderly couples and German newspapers. So, I played solitaire, and read the entirety of Pride and Prejudice on my iPod. I couldn’t get into the book before the summer, but I found I really didn’t care for it once I’d gotten home, either. The familiar, civilized characters were only my good friends after an unpredictable day.

This sensation of loneliness gradually weakened, and finally lost its grip on me entirely, when I was least expecting it. It was a hot, hot day and I was exhausted, nearly out of water, and looking for a place to spend the night. I had been riding through a valley for the last 10k, and it was the sort of valley with no easy way out, where you look around for a gap in the hills, and don’t see one. I was lost, too, having missed the last turn and trying to find a new way to the next town. I finished a climb and arrived at a three-way intersection. I looked to my right, and cursed aloud at the though of climbing that hill. I looked to my left, and cursed silently at the thought of going down the hill, being wrong, and having to climb it. I looked at my map, I looked around. I decided to go left, down the hill.

And at that moment, something happened. Suddenly, I didn’t care whether I was going the right way, or if I would have to turn around. Finding accommodation seemed less important; I knew I could ride until I found what I needed. It was a reckless feeling, and part of me wondered if this newfound resolution was real, or permanent. The rest of me focused on picking up speed. I had gone from somebody who thought they might fancy an adventure, to someone who had been hardened in its fires, and better for it.

I crossed the former border 126 times. I never ceased to be amazed that I was able to chase an invisible line across the countryside, and hop over it whenever I wanted to, nearly three times a day, when untold numbers of people had died trying to do it just once. Sometimes, I was hyperaware of where the former border was in the landscape. I remember riding down a misty section of the Kollonenweg (which is the former East German patrol road right on the border)-I looked up and noticed that the trees on my left were shorter than the trees on my right, and I realized that the short ones were only as old as me, planted in the formerly barren death strip. My map was marked with a thick pink line the whole way through, and I earnestly compared the sights and smells of my surroundings on both sides of it. But sometimes, I got disoriented, and couldn’t tell what side I was on, and sometimes, I didn’t care at all.

I got lost a lot. There were some funny directions in my guidebook and I often found myself backtracking or making up my own path and hoping it would take me somewhere. Once, I followed a hiking trail for two kilometers, deep into a trackless forest with muddy holes and black flies. I was completely, totally lost in the Harz mountains, imagining that I looked like an idiot to anyone who might have seen me pushing a 45-pound bike through tall grass and over tree roots, with a helmet strapped to my head but obviously not riding soon. I was in trouble. Every brush of the wind sounded like an approaching bear and I tried to remember how to fend off different kinds. I kept looking at the map, trying to understand where I’d gone wrong. I became so frustrated that I screamed at the forest and cried pathetically until I found the path again. I even cursed my bike when it poked me, but felt bad and apologized quickly. After a while, I got better at navigation, but it constantly amazed me how wild the borderland was. The old fences didn’t stop for anything, and traversed rough country, hills and valleys far more nimbly than I did on my bike.

[Slide: Daily hours on the bike: 5-7]

On the trail, I loved the morning. Morning meant breakfast, which was always included with my accommodation, and without fail, involved coffee, and rolls with meat and cheese, and if I was lucky, there would be cereal and yogurt, or even musli. Fruit and eggs was another bonus, and twice, my consolation for an overpriced room was salmon on my breakfast plate.

Morning meant a new day on the road and the first, fresh strokes on the pedals meant freedom. I was a nomad, calling no place mine for more than a night, and sometimes I felt an odd, lingering attachment to whatever room I’d rented for the last 16 hours. When that happened, I would force the thought away as I closed the door, melancholy vanquished as soon as I got in the saddle and peddled away from town.

I found a rhythm after a while: Wake up. Breakfast. Pack. On the road by 9. Hope for a snack. Look for a place to stay around 4. Scout the town. If possible, eat ice cream. Write. Upload photos. Eat. Sleep. This sounds pretty simple, but there’s an art to finding the only spaghetti within 5 kilometers, navigating strange cities with a few simple rules (for example, Schiller street and Goethe street are always next to each other), and packing up all my gear in the morning, and this could only be learned by trial and many, many errors.

[Slide: Members of parliament involved: 1]

I’d been in touch with the office of Michael Cramer, a Member of Parliament who has been instrumental in creating the Berlin Wall Trail and initiating the Iron Curtain Trail. He serves on the committee on transport and tourism, wrote my guidebooks, and has practiced automobile-free living in Berlin since 1979. When I arrived in Neustadt on a Friday I finally was able to check my email, and waiting in my inbox was a very special invitation to meet Mr. Cramer in Berlin that Sunday. I was ecstatic, responded enthusiastically with a yes, please, and then frantically started planning a side trip that was a significant departure from my plans.

So, I booked a room for two nights in Berlin, and bought some sketchy train tickets from a machine at the station. And on the 4th of July, endured a 10-hour marathon journey to the capital during which I missed two trains and exchanged text messages with Mr. Cramer to update him on my estimated time of arrival. I finally arrived at the bustling Zoo station around 6 and made my way to Literaturehaus Cafe for the appointment. It had been a hot day, and by this time I was sweaty and totally disheveled, of course I didn’t have any ‘real’ clothes, that were appropriate for meeting an MEP, so I was pretty nervous. But, Michael welcomed me with a handshake and invited me to eat ice cream.

We spent nearly an hour and a half talking about the trail, German history and division, and his understanding of them both. I learned a lot from talking to him, but my favorite part was his description of traveling to and from Brussels, a journey he has made frequently since 2004 for parliament. He told me that he often sleeps on the train, and even today, always wakes up when he crosses the former border. This was an incredible opportunity, and I was flabbergasted by his willingness to spend a Sunday evening hanging out with an American student; he even picked up the bill. As if this were not enough, he gave me his entire collection of guidebooks, including a copy of the Berlin Wall Trail, which I put to good use over the next few days.

At the beginning of the trip, I had some lofty goals and expectations, but on some level, I had to compartmentalize to keep myself sane, and ended up setting two basic goals for the trip: do not spend the night outside, and do not crash. I’m proud to report that I never spent a night without accommodation, huddled in some forest, but I have to report that I crashed 1 and a half times. The real crash happened the day after I got back to Neustadt from Berlin. I was feeling fresh, and came around a turn fast. Around the corner were two metal bars meant to prevent cars from using the trail. I almost cleared them but the laws of physics have very little sympathy for almost. My handlebar just caught the gate to my right and my bike stopped while my momentum carried me forward over the handlebars. I rolled twice and came to a stop. As I assessed the damage, I was surprised not to see blood, and happy to find all my gear relatively intact. I counted myself lucky and continued on.

The half crash happened on a horribly hot day. I was almost out of water, bordering on delirious. My guidebook was constantly telling me about “town centers worth seeing” and “beautiful oak trees” in the landscape, but then I turned the page and saw on the map, not too far away, “Source of the Frankish Saale River.”it was marked a little ways off the trail, and there were a few signs pointing to it, so I decided to go find it. And pretending I was Ponce de Leon after the fountain of youth, I started pedaling over this gentle, grassy knoll, alongside a flowing brook that I couldn’t quite see, but the sounds from which were increasing my agony and thirst. And then I reached a small hump in the grass, the kind where you just need to stand up on the pedal to give yourself enough weight to get over it. But I couldn’t do it. I balanced, perfectly still for a moment, but then slid backwards, and slowly, painfully collapsed on my side.

This was maybe the lowest low of the trip. It was entirely pathetic, my bike sort of half-hugging me, but also pinning me to the ground. After a few moments, I got back up, slowly, bruised. I pushed my bike the rest of the way up the hill until the sound of running water got louder, and I found a small grove of trees surrounding a pond. There was a steady stream of water gushing out of a small hole in a pile of stones. I jumped into the basin and splashed it all over my head and face. It was cold and clean and I hesitated for just a minute before cupping my hands and drinking deeply from the spring. Well, what’s an adventure without a little risk? I drank a full bottle of the spring water, knowing full well I might have hell to pay later, but also aware that I was dangerously dehydrated and needed water right away. It’s not about the crashes, its how you decide get up from them, bandage yourself, and get back in the saddle. The water turned out to be perfectly fine, and my ego the only thing notably bruised.

One of the best parts of the trip was getting to meet all sorts of people. I spent two nights in Bad Sooden-Allendorf, where I just happened to stay at a pension owned by a founding member of the local borderland museum. This is a picture of Viktor that I took when he drove me up to the Museum and showed me a few sites along the way. Viktor and his wife were wonderful hosts and good for conversation in German, French, AND English.

In the evenings, Viktor showed me videos about the border and reunification, and gave me some publications and information in English. The second night, we watched footage he shot himself in January of 1990, when the border was opened in Asbach, the town in this photo. There were hundreds of excited people waiting on both sides of the fence to greet their neighbors, and marching bands from East and West played. At one point, Viktor turned the camera to the side to film a GDR border policeman lighting a cigarette. Viktor paused the VCR and rewound to play this part again and told me that the man had been a real hard-liner, and was a three-star officer, potentially a dangerous enemy. But in the video, he was caught in a relaxed moment, didn’t shy away, and almost smiled.

Before I left, Viktor gave me this pin from an East German policeman’s hat, smiled, and said, “there, you are a member of the People’s Police now.” I was hugely excited to have this artifact bestowed upon me, but also felt the full weight of the history in this little, aluminum badge. I wrapped it up carefully in my bandanna and put it in my saddle bag. We hugged before I hit the trail again.

There were a lot of other characters on the road; I met a professional English/German translator on the streets of Salzwedel when I needed language help more than any other time on the trip. I spent two hours walking through pastures with a woman who claimed to have been kidnapped by East German border guards. I made friends with a guy from Texas who did two tours at Point Alpha in the 70s and 80s. These conversations were a fantastic part of my trip, and there are truly too many stories to relate in this time. Every person I met offered a different perspective on my questions about the border, and helped me patch together a more complete understanding of Modern Germany.

But as different as these voices were, they mostly agreed that divisions remain between East and West. With just three days left to go, this perspective was finally disputed by a well-traveled woman named Nina, who was only a few years older than me. To her, Germany was Germany, all across the country. I don’t know if I can make broad claims from these conversations, but I am convinced that the generation gap is real, and it’s going to take time, continued awareness, and projects like the Iron Curtain Trail, to heal the gaping wound that cut Germany in two for 40 years.

When I was in Berlin, I asked Mr. Cramer whether he considered the Iron Curtain Trail to be a symbolic journey. Well he wasn’t quite sure what I meant, and I realized I wasn’t either. That line of questioning didn’t go very far but I kept thinking about it, trying to put words to what I was doing, trying to figure out how to explain this passion I’d discovered. I realized that one of the reasons I love the Iron Curtain Trail is because it brings intense purpose, challenge, and history to a travel experience. The trail gives you a goal and information, but its up to the traveler to create the meaning and find a way to share it.

Towards the end of the trip, I was feeling pretty good about myself, and I started wondering…’would I want tot do this again?’ And I wrestled with that, because it was really hard. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I thought this talk might bring some closure to the experience, but I realize now that I’m not quite done with it; this has become a fascination that will stay with me for a long time, and I’m so glad to have had the opportunity to start.

New adventures, new blog

Readers, friends, digital wanderers, please find, bookmark, and follow my new blog at www.kateincolor.wordpress.com where I will be writing about my adventures Walking Walls in Israel/Palestine, Cyprus, and Northern Ireland this winter. Also check out my new homepage at www.kateincolor.com

I have no plans to shut down Biking Borders, but won’t be updating very frequently anymore!

Video for Walking Walls!

Help me photograph borders and divisions in Israel, Cyprus, and Northern Ireland this winter. Click here to see more about my campaign and contribute!

Mapping the Contemporary Iron Curtain

Last winter, an intern at Facebook created the above graphic, which represents ten million “friendships” on the social networking site with a thin blue arc connecting the real world locations of the users. The result was astonishing. By plotting this data, Paul Butler created a recognizable world map, which displayed not only Facebook friendships, but also continents, oceans, and countries. Paul wrote about the project and commented, “What really struck me, though, was knowing that the lines didn’t represent coasts or rivers or political borders, but real human relationships.” Yet, a cursory inspection of the map is enough to realize that the lines often DO imitate political boundaries. Although they do not represent borders themselves, the Facebook map reinforces their presence and significance in our lives, which is perhaps more profound than we realize.

Look at this map carefully and you can clearly see the shadow of East Germany in a significantly less-dense field of Facebook users. This map suggests that despite our increasingly globalized civilization, political borders still determine the way we live, work, and socialize in a way that is self-perpetuating. By examining a variety of contemporary maps, it will become clear that although the Iron Curtain fell 21 years ago, it is still a deeply felt reality beyond the traditional political map of Europe.

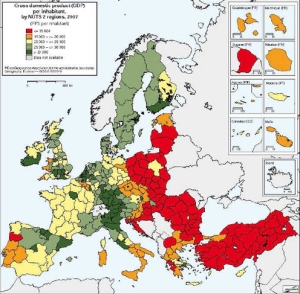

Consider this map of Europe (above) during the Cold War and compare it against the subsequent maps. You’ll see startling similarities.

Contemporary Maps and Statistics

The most startling examples are economic. Unemployment is higher, and income is lower almost across the board in areas once behind the Iron Curtain. Most strikingly, note the presence of our phantom East Germany, sharply distinguished from its western counterpart in each map.

Internet access and broadband connections in households

Internet access and broadband connections in households

The map to the left is about internet access, and how prevalent it is an given region. Again, notice the significant gap behind the Iron Curtain. This statistic seems like the odd man out, but is likely rooted in the economic struggle Eastern Europe faced under Communist rule, and the subsequent discrepancy in technological and industrial development. It also goes a long way toward explaining our Facebook graphic-it’s difficult to have online friendships when you don’t have internet access.

Pupils at primary and lower-secondary education, as a percentage of total population

Here’s another off-topic statistic: countries once behind the Iron Curtain are more likely to have a lower percentage of their population in school at the primary and lower-secondary levels. What does this mean? There are fewer young people in the East. Especially, less young, educated people. The problem of young talent fleeing the East was a large factor in the construction of structures like the inner-German border and the Berlin Wall. It continues to plague these regions today, and the trend will probably continue as long as GDP and economic well-being (and internet access!) is at stake. And this time, there’s no physical border to stop them, only this invisible one, which lures migrants across.

It’s also important to note that there are a lot of maps and statistics from Eurostat that DO NOT show any sort of lingering east/west divide. These include things as diverse as: farming structure, transport infrastructure, and fatal diseases of the respiratory system. And, many statistics can be attributed to things like climate that are much larger than any political border.

However, the maps and the data they represent suggest that overall, Eastern Europe, specifically countries that were east of the Iron Curtain, are still behind their Western counterparts, economically and technologically. Furthermore, it is the lingering effect of Europe’s division that is to blame. Quite frankly, many people would not find it surprising that countries like Poland, Belarus, even the Czech Republic are a bit behind. Yet, the repeated appearance of the phantom East Germany on these maps is strong evidence that the gap is directly related to the Iron Curtain and its continued legacy.

The Recession and Conclusions

This issue has been dragged into the spotlight in European responses to the recent recession. As bailouts and debt were first hotly debated in 2008, Hungarian Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsany and Czech Prime Minister Mirek Topolanek both voiced their fears of a new divide in Europe. Their countries’ economies are struggling, yet they desperately wish to avoid more debt owed to Western Europe. Gyurcsany actually invoked the term “iron curtain” while Topolanek warned against “new dividing lines” and a “Europe divided along a North-South or an East-West line.” Unsurprisingly, the recession hit hardest in weak economies once behind the Iron Curtain. As the Eurozone struggles to pull itself together, it’s increasingly difficult to ignore this touchy fact.

What can we learn from these maps?

- The Iron Curtain lives on as an economic and social gap between East and West Europe and remains tied to an identifiable place on the map.

- Political borders go way deeper than bureaucracy and citizenship. They permeate all aspects of economics, society, daily life, and will continue to do so long after their demise.

- Is the gap self-perpetuating? When considering the data represented in the above maps in conjunction with the Facebook graphic, it’s easy to make the case that the Iron Curtain has spilled into a younger generation, despite the march of globalization. If this is true, it’s hard to predict when its legacy will no longer negatively impact the present day economics and overall well-being of Eastern Europe, especially in under the pressure of a global recession that threatens the stability of the European Economic Union.

Further Down the Road

Since getting back to the States at the end of last summer, a lot has happened. A LOT. Most notably, and relevant to the Biking Borders project…

1. I gave a talk at Carleton in January about my trip, along with my Mullin Prize co-winner, Hunter Knight. I have a DVD of the event and hope to post the talk on this blog soon.

2. I completed two senior integrative exercises in one term. My history comps was a 35 page paper titled “One Border, Two Walls: Conflict and Conceptualization Along the German-German Border, 1945-1972.” The paper explores conflict and perception of the border in Berlin and on the inner-German border, arguing that German division was made clear by developments in rural Germany long before the Berlin Wall was built. My comps project for CAMS can be found online. This project examines the genre of Rephotography as it relates to theory and New Media, using the Iron Curtain as my subject. The website includes a theoretical essay, numerous rephotographs made over the summer, and a Google Earth tour.

3. I have the opportunity to join Professor John Schott and the Carleton CAMS seminar in Berlin this week to help them implement a Rephotography project I helped design that is based on my comps, as well as extend my own work in the genre. The trip will include a bike ride along part of the Berlin Wall, which will definitely qualify as a border bike ride. You can follow the action at historyvision.net, as well as the good old Biking Borders twitter feed.

Needless to say, the German-German border, the Iron Curtain, and borders in general are obviously an ongoing obsession that has consumed much of my academic life and captured my sense of adventure. I hope to keep biking (or maybe walking!) and photographing borders for a long time to come.

Make-Believe: Notes on the Berlin S-Bahn

The Berlin S-Bahn shrieks and howls when it whips around curves and brakes before a station. Many passengers covered their ears, deafened by the shrill voices of the wheels on metal tracks. But I didn’t want to miss a single note. I had wandered into Nordbahnhof, a former border station, barricaded and heavily guarded during Berlin’s division. There was a fascinating display inside that explained how the Berlin Wall extended below the earth’s surface, cutting off S-Bahn lines-potential escape routes-that ran from East to West. I read about the “ghost stations” of Potsdammer Platz and the Brandenburg Gate, which West Berliners could pass through, but not get off. Trains would slow just enough to make out blurry faces of the GDR police guarding the platform before the train would whisk passengers back into the darkness.

Excited by these descriptions, I immediately boarded the S1 to Potsdammer Platz. I wanted to relive this strange experience, or at least pretend to. So I sat on the train, surrounded by ordinary passengers who cringed at the noise of the brakes, talked, and laughed. But I was in a completely different world, imagining the silence that must have gripped passengers on this eerie passage 20 years ago, and debating with myself whether or not to get off at Potsdammer Platz, or ride the whole way under East Berlin, trapped underground. My heart beat faster as the train slowed at the station and I imagined the people waiting to board were guards with guns and grim expressions. The train howled as if to exorcise the ghosts of its past and the doors flew open with a blast of cool air when it finally stopped. As people poured on and off the train, I suddenly stood up and got off, breaking the spell.

Perspective

Mahring to Eslarn

17.7.10

A thunderstorm pounded outside, rain lashing at my window. Groggily, I rolled out of bed to shut the window and listened to the tempest. I pictured myself trying to bike through the storm, getting blown over by the wind and soaked with cold water. I eventually fell asleep for another few hours, fearing that I would be unable to continue right away in the morning. When I woke, the storm had stopped, but ominous clouds still hung in the west, and occasional rumbles of thunder gave me pause as I packed. I decided to leave anyway and try to outrun the storm on my south-easterly route. Greta, the cook, insisted on waking Tereza at eight so she could see me off, and the bed-headed, kindhearted woman hugged me and wished me well. I went down the stairs, looked back to wave, and left the house.

It was a misty, cool morning and steam rose from the wet forest, dissipated through a few weak rays of sunshine. I was riding on a gravely path that took me right next to the border and I kept the Czech Republic on my left, and the sun on my handlebars for several miles. The terrain was hilly, but not impossibly so and I found a rhythm of up and down until I arrived in Eslarn in the early afternoon.

I was exhausted by the time I got a room and took a nap before exploring the town and getting a snack. It was Saturday, and everyone seemed in a good mood. A group of villagers were hard at work painting a house baby blue. I smiled and told them it looked good, with a thumbs-up. I ate dinner in the pension restaurant, where the innkeeper’s Bayern accent was so thick we could hardly communicate. I tried to strike up a conversation anyway, asking about the trophies displayed behind the bar. I was impressed to learn that they were all his, for soccer, and shooting. Then, he disappeared into the kitchen and returned a moment later with a woman. She spoke excellent english and introduced herself as Nina. We hit it off right away and spent the evening chatting over a glass of wine.

We had a lot in common and discussed travel, the USA (she spent nearly a year in Florida and Boston), plans for the future, and of course, Germany’s division. I was excited to speak with someone so close to my own age about our generation’s perception of the former border. She admitted that she didn’t know a lot about the subject, and that Germany, eastern and western, was just Germany to her. She noted that there were some economic differences and lingering stereotypes but they had no hold on her and were beyond her experience. I shared some of my findings and agreed on the challenges of understanding something before our own time, but relevant to older generations. I was really struck by her comment that the border came down “so long ago.” Perspective is everything-these twenty one years have been my whole life, but a blink of an eye in history.

It was wonderful to have such a pleasant and diverse conversation but I was forced to excuse myself around 10 in the interest of getting some sleep. We wished each other well just outside the restaurant and I jogged across the street to the pension, since it was raining again.